Chapter 6

Scaling up climate compatible development

Introduction

How do countries build on success and scale up climate compatible development initiatives? Most practitioners interviewed for this book expressed a healthy degree of scepticism when asked, ”What does it take to scale up a successful climate compatible development pilot?” That’s because, “Climate compatible development requires such a specific approach in each place,” said Patricia Velasco, Latin America coordinator. It is no surprise people wonder how approaches can be copied from one place to another: each community or country faces complex trade-offs among resource uses, among beneficiaries of new approaches and policies, and those who do not benefit but must be compensated.

Notwithstanding these caveats, in its five years of experience, CDKN has seen climate compatible development scale up in several different ways:

- principles rather than specific steps are developed and spread from one place to another;

- a successful project or programme forms the basis for new policies or programmes on a larger scale (province or country-wide); and

- green growth or climate-resilience measures in one sector of an economy (subnationally or nationally) raise awareness of and interest in climate compatible development more broadly in society, catalysing climate measures in other sectors or walks of life.

This chapter explores some of the supporting measures that may be made at national level to support the scale-up of successful pilot projects. It also looks into some of the proactive measures that leaders in climate compatible development can take to promote good practices more widely.

Adjustment of national policies may be needed to support innovations at the local level

Piloting climate compatible development can highlight gaps in the policy framework which need to be addressed before results can be sustained – and before any meaningful scaling up can be achieved. This is the case in Western Province, Sri Lanka, where CDKN supported action research into the benefits of urban agriculture and forestry (see Integrating urban agriculture and forestry into climate action plans: Lessons from Sri Lanka’ and Background paper comparing the Sri Lankan experience with that of Rosario, Argentina).

Urban agriculture and forestry are promising approaches to tackling the triple challenges of climate change mitigation and adaptation and food security for the vulnerable residents of cities in developing countries. The research by the RUAF Foundation documents how urban agriculture and forestry can help cities to tackle these challenges simultaneously by:

- reducing vulnerability and strengthening adaptive management by diversifying urban food and income sources and reducing dependency on imported foods;

- maintaining green open spaces and enhancing vegetation cover in the city with important adaptive (and some mitigation) benefits; and

- reducing cities’ energy use and greenhouse gas emissions by producing fresh food inside and close to the city and enabling the recycling of urban resources (e.g. organic waste) in agriculture.

Western Province is the first provincial government in Sri Lanka to include urban and peri-urban agriculture and forestry in its climate change adaptation action strategy. The province is promoting the rehabilitation of flood zones through farming as a strategy to improve storm water infiltration and mitigate flood risks. It also supports local agriculture to reduce dependency on imports; lower greenhouse gas and energy requirements for food production, transport and storage; and improve food security and livelihoods.

However, the research team found that future scaling up of these interventions will need new urban design concepts and the development of a provincial climate change action plan, in parallel with a revision of local and national policies. Until now, national policy has posed an obstacle to scaling up these new practices.

The national Paddy Act has allowed for paddy cultivation only in assigned areas. The Act needs to be revised to promote and support new production models for mixed cultivation of rice and vegetables that can increase income and promote more environmentally sustainable and climate-compatible forms of production. These would include traditional saltwater-resistant rice varieties and measures to maintain the natural drainage functions of paddies. The process of policy revision is currently under way and builds on awareness-raising, impact monitoring and broad stakeholder participation.

Decision-makers need to be convinced by good documentation and first-hand experience

Effective documentation of success factors in pilot projects is essential if local achievements are to leverage larger-scale changes in policy and practice. Quantitative measures (‘killer statistics’) work the best. CDKN’s best examples of scaling up are from projects that have demonstrated lives and assets saved in the face of extreme weather events, and greenhouse gas emissions saved at low or no cost, or with financial gains. It is not surprising that these metrics would make a compelling case.

An example from India shows how careful monitoring and documentation of quantitative results – and the effective presentation of these metrics to government policy-makers – has proven decisive in moving from the pilot project level to policy, or even legislative, reform.

In the city of Ahmedabad, Gujarat, scientific assessment of the effects of extreme heat on excess morbidity and mortality, together with extensive engagement efforts by the research and non-governmental partner organisations, has proven definitive in changing government actions during heat waves. Extreme heat presents a significant threat to the health, lives and livelihoods of residents, especially of those living in slum communities or working outdoors.

Compared to floods or earthquakes, extreme heat is a ‘quiet hazard’. Before 2010, a lack of awareness about heat-related health risks among government officials and citizens alike meant that little was done to tackle the threat. Then, a punishing heatwave hit the city in May 2010, and a project by the Natural Resources Defense Council, Indian Institute of Public Health–Gandhinagar and the Public Health Foundation of India was able to demonstrate that 1,300 excess deaths occurred during the heat wave period. Following the heat wave, the partners held workshops with municipal officials to raise awareness of its impact on the city.

Working closely with the city government, the project assessed the potential risks from extreme heat over the coming decades in the context of climate change, especially for the most vulnerable groups, and developed a set of innovative strategies to tackle the problem. Risk-informed decision-making by CDKN’s Emily Wilkinson and Alonso Brenes of the Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales details this experience, as does the CDKN documentary film Beat the heat.

With no temperature gauge in the city, and no system in place to monitor heat impacts on health and mortality, city officials were not fully aware of the extent of the heat wave’s impact until presented with heat- and mortalitycorrelated data. This information then prompted action. Thanks to the project in Ahmedabad, extreme heat has been recognised in Indian national policy as a disaster risk, and this should improve awareness across the country. CDKN is among several donors supporting a scaling up of such analysis and policy engagement in other Indian cities. CDKN’s India programme manager says that the Inside Story on Ahmedabad’s experience, which systematically documents the steps taken, is a major communication asset in bringing the lessons to other cities. The partners say a major challenge remains: it tends to take an extreme event and preventable deaths to gain the attention of city officials elsewhere. They are working hard to convince other city governments to put disaster preparedness measures in place before another deadly heat wave strikes.

Scaling up community-based adaptation: Lessons from CDKN experience

A CDKN working paper, ‘How to scale out community-based adaptation’, pulls out the following key elements as having been pivotal to successful scaling up in adaptation projects:

- Documenting evidence and learning – having a strong monitoring, evaluation and learning framework in place in order to present compelling evidence of achievement, which makes the case for action elsewhere.

- Ensuring the core objective of building adaptive capacity remains – taking care to retain successful elements of the initial project that emphasised the development of the community’s local capacities for adaptation.

- Networks and partnerships as the cornerstone – linking community practitioners with external organisations, research institutes and businesses (domestic or international) that have the ability to spread good ideas beyond the original project area.

- Finding cost-effective institutional channels and finance mechanisms for scaling out – looking not only to government schemes and policies as a potential route for scaling out, but also to the private sector, which may offer even more effective networks and capability.

CDKN and its partners have also found that giving political leaders a first-hand experience or ‘witness trip’ to see problems and solutions provides a strong impetus for climate-related policies (see Box – Action for Climate Change Resilience in Africa).

Action for Climate Change Resilience in Africa (ACCRA) improves prospects for remote communities through active engagement of national policy-makers

Bundibugyo is located in the western region of Uganda. It is so mountainous that the area is prone to immense soil erosion and destructive landslides. In recent years, flooding has become more common as a result of climate change – and causes further landslides.

Poor land-use practices such as large-scale deforestation, burning vegetation, and lack of soil conservation structures makes landslides worse.

Backed by CDKN, ACCRA carried out a study which showed that district development plans did not reflect the challenges posed to communities by climate variability, disasters and change. Most importantly, the district development plan is a key instrument in determining funding allocations from local and national sources.

District plans lacked climate-resilience because they were disconnected from national frameworks such as the Disaster Management Policy and the National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA). District government staff were neither aware nor involved in the development of the national policies. ACCRA also found that district planning was carried out in isolation from line ministries with no technical support. The funds from central government are conditional on districts’ meeting five national priorities and it is difficult to mobilise such funds to address emerging local crises.

As part of the capacity-building activities, ACCRA facilitated a community-level field visit to Bundibugyo for six key ministry representatives, aimed at increasing national-level understanding of climate adaptation issues on the ground, and strengthening the linkages between national- and local-level governments. “The visit to Bundibugyo allowed us to see the impact of climate change and understand what is needed,” commented Annunciata Hakuza of the Ministry of Agriculture. “The research results will help inform our future policy.”

ACCRA also funded training of the district planning teams on integrating climate adaptation and disaster risk reduction (DRR) into their sector plans. These measures were later included in the five-year District Development Plan. The planning exercise was facilitated by representatives from the Ministry of Water and Environment and the Ministry of Local Government, the National Agricultural Research Organisation and the Office of the Prime Minister. For the first time, all 11 sectors and specific department heads in the district gathered to discuss and plan together. The result was a comprehensive five-year District Development Plan (2011-2015) integrating adaptation and DRR measures.

Jockas Matte, the district senior environment officer commented, “Before, my colleagues thought that climate change was just an environmental issue. Now all of us planned together, [and] as a result, we now have a plan that addresses climate change and we share responsibility.” Crucially, the district staff found it was possible to plan and implement climate adaptation and DRR activities within existing budget frameworks.

The chief administrative officer noted that, “with support from ACCRA and the links it helped create with Ministry of Water and Environment, we have been able to attract additional NAPA funding of 123 million Uganda Shillings”. It is expected that implementation of the NAPA will touch the livelihoods of the most vulnerable. Some of the planned activities include soil and water conservation (terraces, tree planting), formulation of by-laws, fuel-saving stoves, as well as learning visits and awareness-raising.

The district has become a learning lab for national ministries and neighbouring districts which have closely followed the process. “ACCRA has had a profound impact on our district,” commented David Okuraja. “Our district has generally been viewed as isolated, affected by war and stigmatised by disease outbreaks such as cholera and Ebola. Few national-level decision-makers ever came here. But ACCRA helped put Bundibugyo on the map. Now we talk directly to ministers!”

In Latin America, a CDKN team is following an approach to documentation called sistematización de experiencias (roughly translated as ‘systematisation’ in English). “[Its] fundamental principle is the importance of the collective construction of knowledge that is based on the value of generating learning experiences for people and groups,” says Maria Jose Pacha, the Latin American knowledge and learning coordinator. “To transform this learning knowledge (which most often goes unnoticed by the actors themselves), it is necessary to develop a methodology aimed at fostering recognition, reflection and developing lessons learned.”

The method promotes encounters among actors to analyse their experiences, review the rationale behind them, and foster lessons learned. The technique emerged in Latin America in the mid-1970s and integrates learning concepts from popular education and tools for social intervention, such as participatory action research. It encourages critical and reflective interpretation of the processes of transforming behaviour, where the processes are as important as the product. Knowledge emerging from collective reflection is packaged into neat, sharable products. The triple advantage of this approach is that it:

- allows professionals and communities working in projects to draw conclusions from their own experiences;

- helps identify lessons learned about what works and does not work; and

- develops capabilities that support monitoring and dissemination of projects.

In mid-2015, CDKN convened practitioners from 10 climate compatible development projects around Latin America and the Caribbean to reflect on their experiences in urban climate-resilience, using this methodology. The event generated cross-cutting learning and created the crucible for an emergent community of practice for Latin American urban resilience practitioners. In the words of one participant, “It is encouraging to meet people with the same vision and is important to maintain and nurture links, which can lead to impact with the authorities or local actors.”

Narratives from high-profile leaders promote success

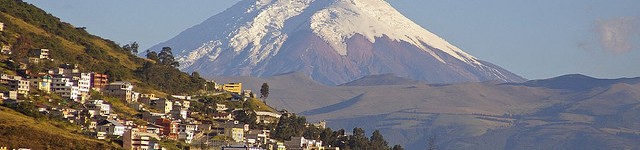

As discussed in the Box, there is a role for political champions in demanding accountability for the delivery of climate compatible development. We have also noted the importance of political champions in scaling up successes. Three city-level examples from Latin America, and a nationwide example from the Caribbean, are instructive. The capital cities of Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru are vulnerable to climate change, partly due to their dependence on water from retreating Andean glaciers for human consumption, industrial use, hydropower production, agriculture and other uses. A project supported by CDKN and the Development Bank of Latin America assessed the cities’ carbon and water footprints and then the municipalities prepared action plans and pilot projects to tackle the most critical issues.

The project team for the Andean Cities Footprint Project noted the role of local political leaders in celebrating success. They say, “Mayors and other high-level officials in the three cities are talking in terms of footprints and how having generated carbon and water-use data – data which didn’t exist before – enables more informed decision-making oriented towards climate compatible development.”

In La Paz, the mayor hosted a public event where he presented the 10 actions to reduce municipal government footprints, providing investments in prioritised areas such as the municipal slaughterhouse. He, and other high-level city officials, were satisfied with the results of the project, since it confirmed that current efforts in the transport, residential and waste sectors were well-directed, not only from the traditional standpoint of development, but also for climate change mitigation and adaptation.

In Quito, the footprint ‘language’ has been appropriated by the mayor and high-level city officials, and has influenced various city plans related to water, land use and carbon in forests. Offset mechanisms for the carbon and water footprints of the city, developed with public and private actors, are in the design phase. The footprints also catalysed the mayor’s proposal to create public–private partnerships as a strategy for city development, and companies on the frontline of climate change efforts have been officially recognised. The city has set a target to reduce its carbon footprint by 5% by 2019.

In Lima, during preparations for COP20 in December 2014, the Cities Footprint Project organised events with Peru’s Ministry of Environment. The COP20 agenda was influenced by including ‘cities’ as one of the five main discussion topics. The project is believed also to have influenced the decision to launch the National Programme for Sustainable Cities by the Ministry of Environment. Finally, financing for urban climate compatible development projects is starting to gain momentum with the municipal government. Insights from La Paz, Quito and Lima are all brought to life in the CDKN film Cities Footprint Project: Urban impact.

A CDKN Inside Story on the extensive uptake of solar water heating in Barbados documents how long-term fiscal and regulatory certainty for manufacturers and customers has been fundamental to uptake. However, there were initially cultural barriers and unfamiliarity with the technology which hampered customer acceptance. The author concludes that, “Persuasive champions who are able to speak to communities, together with effective marketing strategies, are vital for consumer acceptance of the technology.” As a result of this combination of stable and certain government policy and championship by the prime minister and other high-profile people, more than 50,000 systems have been installed in this small country and they save consumers US$11.5-16 million per year.

Professional regulations and codes help scale up climate-compatible development

Successful pilot projects can provide the test beds for developing climate adaptation and mitigation measures, and these can drive the development of technical regulations and codes which embed the climate measures more broadly in sectoral practice. An example is the Sheltering from a Gathering Storm project, which led to the adoption of new housing codes in Da Nang, Viet Nam.

Shelter accounts for the highest monetary losses in climate-related disasters and is, therefore, a significant cost for governments and other stakeholders working on disaster risk reduction or reconstruction. Shelter is also often the single largest asset owned by individuals and families, so the failure of shelters to protect people from hazards is a significant risk to lives and livelihoods. Sheltering from a Gathering Storm was a two-year research programme targeting peri-urban areas in India, Pakistan and Viet Nam. It identified practical solutions for resilient shelters, and conducted research on long-term economic returns of investing in such shelters, focusing on cities at risk from typhoons, flooding and extreme heat. The project was led by ISET-International in partnership with Hue University (Viet Nam), Gorakhpur Environmental Action Group (India), ISET-Pakistan and ISET-Nepal. Among other things, this research demonstrated that simple, resilient housing designs and features cost-effectively reduce losses suffered by vulnerable communities from floods, storms and extreme heat. A lack of access to affordable financing, coupled with limited awareness and training of builders, were identified as primary barriers for vulnerable populations to access climate-resilient designs.

In Viet Nam, the research programme worked closely with a Rockefeller Foundation-funded project facilitated by the Women’s Union of Da Nang, which provides loans to low-income households (mostly women) to build climate-resilient shelters. The innovations identified during the project informed the loan programme, and 244 homes with typhoon-resilient features had been built in the city with affordable financing well before the end of the project. When Typhoon Nari hit the city in 2013, all 244 homes built as part of the programme withstood the storm, while hundreds of other homes nearby were heavily damaged.

These visible increases in disaster resilience prompted the Da Nang City Government’s decision to integrate climate resilience into its building regulations. The policy requires all new housing programmes within the city limits to apply climate-resilient principles. This decision was taken on the basis of the research findings, the high degree of engagement with stakeholders throughout the project, and the demonstrated short-term benefits of investing in climate-resilient structures.

Professional networks catalyse action through learning and peer exchange

National or international networks of local actors can form communities of practice – sometimes on a quite technical level – and trial approaches that are then modified and replicated within and across borders (often with external public and private funding). In this way, climate compatible development initiatives are piloted at local level and inspire replication at similar scale elsewhere – for example, city-to-city learning. Examples are the Urban Low Emission Development Strategies (LEDS) initiative spearheaded by ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability, or the Rockefeller Foundation-backed ACCRN network (the influence of which has been documented in the CDKN-supported case study on the flood-resilience project in Gorakhpur, India).

The Low Emission Development Strategies Global Partnership (LEDS GP) is a vibrant example of a community of practice, now in its fourth year, which has US Department of State funding for sectoral working groups and regional platforms to explore many facets of LEDS. The working groups and platforms develop joint tools, knowledge-sharing webinars and events, and provide technical assistance to developing country members. More than 180 organisations and individuals are members of the partnership.

The Latin American Platform on Climate (LAPC), created in January 2009 with support from the AVINA Foundation, gathered 20 civil society organisations from 10 countries of the region (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Costa Rica and Uruguay). LAPC seeks convergence, dialogue and coordination among diverse stakeholders committed to finding answers to the challenges – those that call for radical changes – which humankind is now facing. The LAPC is leading the construction of a more equitable world that acknowledges the boundaries of nature, to overcome the threat of climate change and construct new ways of living on this planet. CDKN is supporting the platform through a project that focuses on five Latin American countries (Bolivia, Brazil, Costa Rica, Paraguay and Uruguay) and aims to strengthen civil society capacities and generate adequate space to build national climate change agendas in a participatory way and through multi-sectoral approaches. This process will also provide learning with regard to the tools and conditions as well as key success factors that should be considered when developing multi-sector, participatory processes for tackling climate change.

Technical tools support scaling up

Technical tools for measuring climate vulnerability and resilience, or for measuring greenhouse gas emissions, can provide a basis for climate compatible development decisions. Such tools are normally developed with a view to replication elsewhere. The practitioner network LEDS GP, described above, runs sectoral working groups which provide the focus for extensive peer exchange and learning on practical aspects of LEDS. It is notable that such a strong focus of these international working groups should be the development of tools, and also of ‘toolkits’ or ‘tool filters’ which allow technical users to select the most appropriate from a variety of tools available. Participant feedback indicates that decision support tools can provide the helpful guidance necessary to catalyse new climate activities beyond initial pilot levels.

This is precisely the case for a CDKN-supported project to carry out participatory carbon and water footprint assessments for the local governments and the metropolitan areas of three Andean cities. CDKN supported a project team at Servicios Ambientales S.A., Bolivia to work with the municipalities of Quito (Ecuador), La Paz (Bolivia) and Lima (Peru) in the Cities Footprint Project in 2012-2015 – as detailed above. The results of these assessments led to the development of various action plans for each municipality, with specific footprint reduction targets for carbon and water use.

The project found that citywide carbon and water footprints “have proven useful for decision-making in urban planning and management to help define footprint-reduction goals and project portfolios” (a CDKN Inside Story describes the tool and process in some detail).

As a result of project implementation, demand for similar assistance has come from several cities in the region. The team concludes that producing a Spanish-language toolkit that presents the methodologies used for the carbon and water footprint and the results of its application, has been instrumental in generating this broader demand.

Programmes should be planned from the beginning for scaling up

The mainstreaming of disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation across government agencies is a slow process. The design of Bangladesh’s Comprehensive Disaster Management Programme (CDMP) in two phases acknowledged this reality (see CDKN Inside Story Bangladesh’s Comprehensive Disaster Management Programme). In the two and a half years that Phase I was active, it piloted programmes that could be scaled up as they became feasible. Phase II, designed as a four-year programme, will continue to scale up these programmes to achieve its strategic outcomes.

One of the most important findings from CDKN’s evaluation of its own overall programmatic impact is that individual initiatives, however innovative and effective, are rarely successful at scaling out or up unless this has been built into project design right from the beginning. This is a key message if we are to achieve transformational change at scale.

In Bolivia, a small pilot-scale project to pay land managers for maintaining ecosystem services was initiated with a view to expanding rapidly in other localities. It has succeeded in doing so, and now stands on the brink of becoming law in one Bolivian department (equivalent to a province).

As in many other Latin American countries, deforestation in Bolivia’s upper river basins has caused a lot of environmental problems with local to global impacts – from soil erosion and declining water quality to greenhouse gas emissions. A CDKN-supported project in the Bolivian Department of Santa Cruz is helping to tackle all these problems at once, by enabling land managers in the upper catchments to receive compensation for conserving forest lands (see also Chapter 4). The Reciprocal Water Arrangements (known as ‘ARA’ for the Spanish acronym, Acuerdos Recíprocos por Agua) commit land managers to a range of eco-friendly practices. These include conserving the forest, stopping polluting livestock practices and enhancing the biodiversity and forest carbon of their land. In exchange, they receive in-kind compensation that boosts their incomes and significantly improves their livelihood prospects.

ARAs are private agreements between water cooperatives and landholders in priority catchment areas that are designed, managed and monitored locally. The improved land use practices that have resulted from these agreements are helping to tackle climate change, and the incentives built into the schemes have made them particularly successful: downstream water users are benefitting from better water quality and upstream participants are reaping material rewards. In the past two years, local and donor funds have compensated landowners’ conservation efforts with barbed wire, cement, fruit tree seedlings (e.g. apples and plums), beekeeping equipment, plastic piping, water tanks and roofing materials. The ARA schemes are thus unlocking vital resources for upland farmers who otherwise risked becoming increasingly marginalised by their lack of capital. Since the first Bolivian ARA was developed in Los Negros, more than 50 municipal governments and water cooperatives across the Andes have joined the movement. According to the architects of the scheme, the built-in simplicity of the schemes makes them suitable for replication.

In contrast to other Payments for Ecosystem Services schemes, ARA schemes do not rely on extensive hydrological and economic studies to define the right payment levels, writes Asquith, in his case study report. Instead, they “attempt to formalise pro-conservation norms by publicly recognising individuals who contribute to the common good by conserving their ‘water factories.’ They respond to one of the key findings of behavioural economic theory, which is that ‘money is the most expensive way to motivate people. Social norms are not only cheaper but often more effective as well.’”

At sectoral level in Colombia (see Box), a methodology was developed and piloted for one agricultural area of the country with a view to applying lessons elsewhere – it has now been rolled out successfully in other parts of the country and has informed a national adaptation plan for agriculture.

Developing ways to measure vulnerability and scale up adaptation in Colombia

In Colombia, the Second National Communication has identified the agricultural sector as one of the sectors to receive the greatest impacts of climate change.

This is especially important as the agricultural sector represents 9.1% of the nation’s GDP. The Ministry of Agriculture together with the Ministry of Environment decided to undertake a vulnerability analysis in the Upper Cauca region – one of the most important agricultural regions of Colombia – to pilot a methodology for the country. This analysis was conducted by the International Center for Tropical Agricultural (CIAT in Spanish), National Centre of Coffee Research (CENICAFE in Spanish) and the universities of Cauca and Caldas with the support of CDKN, and involved more than 600 experts and representatives of the agriculture and climate change sectors. The project generated the first multi-dimensional methodology to understand the climate vulnerability of six crops at municipal and departmental levels.

The Upper Cauca River basin was chosen for this exercise due to its combination of four factors:

- Economic importance: The Upper Cauca region is the top producer of sugar cane in Colombia and also includes the coffee region of Colombia. It generates a significant percentage of the country’s GDP.

- Vulnerability: The region hosts agricultural sub-sectors identified as highly vulnerable and representing production systems from small subsistence farms to much larger enterprises with high technology, as well as diverse temperatures ranges of the altitudes characterising Colombia’s Andean and inter-Andean zones. These include sub-sectors growing cocoa, potatoes, beans, coffee, rice, sugar cane and fruits, and pastures for different types of livestock, as well as forests, including bamboo, for timber and derivatives. This area has some of the most diverse ecosystems in Colombia including Páramo and snow peaks as well as lower lands, all highly vulnerable to climate change.

- Poverty: This area features large agricultural companies as well as indigenous and rural communities of low-income families who live on what they can grow on their small farms. This area is part of the Coffee Belt and has the country’s highest unemployment rates. In turn, the department of Cauca has the most extreme conditions of poverty among Colombia’s departments. The Human Development Index averages 0.76 for the whole country, but only 0.68 in Cauca.

- Institutional capacity: The area has strong agricultural and research institutions capable of undertaking climate vulnerability research. Another consideration taken into account was the institutional strength of the federations representing production sub-sectors such as coffee, cacao, sugar, rice and other cereal grains, cattle, fruits and vegetables, timber and bamboo and their derivatives. They all contributed with information, human and logistical capacity, and in-depth knowledge on their sub-sectors

The AVA project (Adaptation, Vulnerability and Agriculture) resulted in a complex model for the six crops, five departments and 99 municipalities involved. This robust analysis is now being used for other regions and further development of adaptation models for the agricultural sector. The AVA methodology was scaled up, refined and used in other regions of the country through a cooperation agreement between CIAT and the Ministry of Agriculture. (For more information see Inside Story Analysing vulnerability: a multi-dimensional approach from Colombia’s Upper Cauca River basin and web platform www.ava-cdkn.co)