Chapter 3

Planning climate compatible development

Introduction

In the previous chapter, we looked at a range of factors, including political factors, which are at the heart of making the case for climate compatible development. In this chapter, we look at some of the cross-cutting macroeconomic and sectoral entry points for climate compatible development. We then assess the ‘ingredients’ of successful planning processes that reconcile the informational and political needs of different interest groups and enable them to move forward together.

Macroeconomic and sectoral entry points for climate compatible development

Macroeconomic stability and growth

In his Ten propositions on climate change and growth, Simon Maxwell takes as the departure point, “The first approach to policy for low-carbon growth is that an economy must be equipped for growth in a rapidly changing global economy. This is always true, and growth policies need to recognise that technologies and institutions can change economic prospects very quickly. Climate change and climate change policy simply add further elements.” He explores some of the specific opportunities for growth that will be afforded to countries used as illustrations (e.g. lithium reserves in Bolivia that will support the expansion of batteries in solar power technologies).

Setting action on low-emissions development and climate resilience at the heart of macroeconomic planning is well illustrated by Rwanda, where “most of the country’s climate-related policy milestones and strategic frameworks were developed in the last five years and are embedded in Rwanda’s national development frameworks. In the case of Vision 2020 – Rwanda’s long-term development strategy – its 2012 revision was informed in part by the increasing burden of climate-related impacts (e.g. droughts, floods and landslides). Similarly, Rwanda’s latest Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy 2013-2018 (EDPRS II) … prioritises ‘green economy’ transformations such as a green city pilot to test and promote new approaches that respond to Rwanda’s rapid pace of urbanisation.”

Ethiopia has similarly set out a national vision in which its desired progression to medium-income country status by 2025 is predicated on low-emission, climate-resilient growth. The economy-wide strategy is termed the Climate Resilient Green Economy (CRGE) Strategy. Its conclusions have been embedded in Ethiopia’s INDC, as submitted to the UNFCCC. According to the analysis by Climate Action Tracker, this INDC is one of fairest and most ambitious.

The CDKN-supported Green Growth Best Practices Initiative found that “Ethiopia’s main framework for green growth … considers synergies between economic development, poverty reduction, climate change mitigation and resilience across all sectors of the economy … Ethiopia used a broad analytic framework for assessing green growth benefits. An Integrated Assessment Model was used for macro-economic impact such as the loss of GDP from climate change impacts in the agriculture and energy sectors. The benefits (and costs) of each option were assessed using multiple criteria that ranged from economic cost-benefit ratios, to qualitative assessments of the benefits for biodiversity and poverty reduction. A relatively basic spreadsheet-based analysis was used to assess sector specific benefits.”

Adaptation

In the developing countries with few historic emissions and great development needs, an ‘adaptation-based mitigation’ approach is garnering attention and shows promise of expansion. Here, the primary policy driver or entry point is increasing the resilience of development solutions: there is demand for climate change adaptation, and mitigation elements are included as a side benefit.

For example, Fiji is a small country with relatively little forest cover and therefore somewhat modest potential for ‘Reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation’ (REDD+, a ‘mitigation first’ approach to finance and development). Rather, its predominant climate concerns are with adaptation, and its development priority is to tackle chronic poverty. However, country stakeholders, supported by a regional programme of the German agency for international cooperation (GIZ), recognised that a Fiji REDD+ programme could be “set in a broader context than what might be typical of REDD+ policy work in larger, more heavily forested tropical countries” (CDKN Inside Story Going after adaptation co-benefits: A REDD+ programme in Fiji). Author Murray Ward reports,

“Finance for readiness and eventual REDD+ activities can also contribute to a range of sustainable land management priorities, such as watershed protection, flood mitigation, water security, drought mitigation, mitigating land degradation, coastal forest management (including the protection and enhancement of mangroves) and biodiversity conservation. Seen in this light, the high costs of developing REDD+ readiness can become justifiable for more developing countries and donor agencies.”

Perhaps what makes this ‘small is beautiful’ case study stand out is that Fiji’s REDD+ plan contains explicit objectives across the domains of climate mitigation, adaptation, and human livelihoods and empowerment, including gender equality. As a plan that is intended to attract REDD+ financing, it must include specific objectives for delivering additional carbon storage and sequestration beyond a business-as-usual scenario, and the systems to measure this additional achievement. Yet, because this plan was formulated with the help of a GIZ regional adaptation programme and with endorsement from across Fiji’s government agencies, explicit adaptation and human development goals are the driving force.

El Salvador has developed an ‘adaptation-based mitigation’ approach, also based on the principle that adaptation activities generate co-benefits for mitigation. According to PRISMA (Programa Regional de Investigación sobre Desarrollo y Medio Ambiente) in a study for CDKN, the approach enables the country to tailor climate action to its specific needs: “for El Salvador, the priority is addressing the country’s high levels of environmental degradation which makes it particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate variability and extreme weather events. Accordingly, El Salvador’s efforts to reduce environmental degradation and vulnerability, (such as, conservation and management of soil and water, expansion of agro-forestry systems and the promotion of sustainable agricultural practices), also highlights how these efforts increase the capture and storage of carbon as well as reducing greenhouse gases emissions. The adaptation-based mitigation approach seeks to engage and impact change at a landscape level, while requiring that the needs for adaption dictate the location and extent of mitigation efforts. This approach has been the basis for the design and implementation of the National Program for the Restoration of Ecosystems and Rural Landscapes (PREP) in El Salvador and the development of the country´s REDD+ preparedness proposal.”

Energy access

Decarbonising the energy sector – that is, providing energy services via renewable resources – is an unavoidable step on the global pathway to a secure, net-zero emissions world, because energy currently contributes some 40% to the global footprint of greenhouse gas emissions (see 3 steps to decarbonizing development for a zero-carbon world and the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report, volume III Mitigation of climate change). Energy access also provides the entry point for a range of important policies that are ‘climate compatible’ in the fullest sense of delivering triple wins for development, climate adaptation and mitigation.

A range of CDKN-commissioned research and programmatic insights show how developing countries are successfully piloting low-emission, climate-resilient planning in the energy sector. These initiatives are often driven by the need to expand energy access in order to provide basic development benefits and to underpin economic growth, as in Tanzania, where a lack of reliable access to electricity is a significant barrier to economic development and job creation. Only 14% of the population has access to electricity; in rural areas the electrification rate is around 2%. Power outages are frequent – especially during droughts, which cripple the hydroelectric power on which most of the country depends. A CDKN Inside Story, Achieving development goals with renewable energy – the case of Tanzania, explores how the country’s Small Power Projects (SPP) programme supports deployment of decentralised renewable energy solutions such as solar photovoltaic systems. Although only running at a pilot scale, the programme has contributed to Tanzania’s climate compatible development by improving access to reliable electricity, particularly in rural areas. Greenhouse gas emissions have been reduced, as the programme reduces reliance on diesel- and gas-powered generators during power outages, and climate resilience is strengthened because decentralised solar power provides an alternative to hydropower systems that are vulnerable to drought.

Because the robustness of energy generation and power transmission systems can be profoundly affected by climate impacts such as sea level rise, drought and high temperatures, it is important that countries assess the climate resilience of their energy systems as well as their emissions profile. For this reason, a CDKN-supported project in Benin, Mali and Togo has used a comprehensive planning tool, the TIPEE tool, to rate energy development options for climate mitigation, adaptation and development benefits.

NAMAs provide source of finance for improved energy services

The UNFCCC’s invitation to developing countries to submit nationally appropriate mitigation actions (NAMAs) for consideration for donor funding has proven a further impetus for the development of programmes and projects in the energy sector.

A NAMA is defined as “any action that reduces emissions in developing countries and is prepared under the umbrella of a national governmental initiative. They can be policies directed at transformational change within an economic sector, or actions across sectors for a broader national focus. NAMAs are supported and enabled by technology, financing, and capacity building and are aimed at achieving a reduction in emissions relative to ‘business as usual’ emissions in 2020”.

CDKN has helped Kenya to develop a NAMA for the expansion of geothermal power and the Indonesian province of West Nusa Tenggara to develop a NAMA for renewable energy development, which are documented in the Inside Story Nationally appropriate mitigation action to accelerate geothermal power: Lessons from Kenya and Climate and Development Outlook: Indonesia special edition.

Energy security

A country’s or region’s desire to reduce its dependence on expensive, imported fossil fuels is also a strong driver for climate compatible energy policies. Ellis, Cambray and Lemma describe how, “In the Caribbean, CDKN funded the development of an Implementation Plan for the Caribbean Community’s (CARICOM) Regional Framework for Achieving Development Resilient to Climate Change. This was formally adopted by heads of state in 2012. Although the case for action was framed around adaptation and resilience, the consultation process revealed that some countries spend 30-40% of foreign exchange earnings on fossil fuels. Reducing the cost of energy, in particular for the poorest of those countries, was a key driver for action on climate compatible development” (Drivers and challenges of climate compatible development, 2013).

Public health

The range and behaviour of disease vectors is altered by climate change. Effective medium- to long-term public health planning will need to take account of climate change impacts and, therefore, be more climate resilient than at present. For example, the geographic range of disease-bearing insects and parasites will change, as these species’ distributions shift in a changing climate. Water-borne diseases may pose new risks to human populations as, for instance, increasing incidences of flood and drought threaten the provision of freshwater and sanitation. CDKN’s Inside Story on participatory planning in Maputo, Mozambique describes exactly how local communities have identified the relation between solid waste, urban sanitation and flooding, and the consequences for diarrhoeal disease as a priority area for adaptation action.

Climate mitigation programmes in the energy and transport sectors offer well-documented gains for public health (reduced asthma and lung disease, etc.) via improved air quality – this is the case whether polluting vehicles are replaced with low-carbon ones in an urban setting, or whether indoor air pollution from fires and traditional cook-stoves is reduced through low-emission alternatives. There may be additional co-benefits depending on the mitigation intervention involved, such as reduced traffic congestion and improved economic productivity in the case of low-emission transport systems, or improved personal security and reduced risk of violence against women and girls for those householders who no longer have to walk far to collect firewood. All of these have aspects that further improve people’s wellbeing. Some of these benefits may be quantifiable in economic terms or other quantitative indicators, such as the increased number of ‘disability adjusted life years’ for a healthier population with less disease. Other quality of life benefits may not have a price tag but could help overcome resistance to climate compatible development policies and provide rallying cries for alliance building.

The risks of low-emission action must also be carefully evaluated by decision-makers, as in other sectors. For example, incentivising bicycle use boosts zero-carbon transport and exercise, both of which are good for public health, but without enforcement of traffic regulations and safe places for cycles to operate, the incidence of road traffic accidents involving cyclists could increase.

Freshwater access and management

Many of the projected increases in extreme weather and climate events will have a direct impact on water resources, for example:

- It is likely that the frequency of heavy precipitation will increase in the 21st century over many regions.

- There is evidence, providing a basis for medium confidence, that droughts will intensify over the coming century in southern Europe and the Mediterranean region, central Europe, central North America, Central America and Mexico, north-east Brazil, and southern Africa. Confidence is limited because of definitional issues about how to classify and measure a drought, a lack of observational data, and the inability of models to include all the factors that influence droughts.

- It is very likely that average sea level rise will contribute to upward trends in extreme coastal high-water levels causing coastal flooding and saltwater intrusion into the groundwater.

- Projected precipitation and temperature changes imply changes in the frequency and severity of flood events in many regions of the world.

In Africa, parts of the continent already face acute water shortages. CDKN has been helping the African Ministers Council on Water and the Global Water Partnership to meet the Sharm el-Sheikh Declaration on Water and Sanitation adopted by African governments in 2010, which pledged to accelerate action to improve people’s access to drinking water and sanitation. Through the Water, Climate and Development Programme (WACDEP), they aim to increase African countries’ capacity and knowledge to integrate water security and climate resilience into development planning.

From 2011 to 2013, the partners produced a framework to help decision-makers to develop finance strategies and investments that would promote water security in a changing climate. They also created a technical tool, users’ guide, capacity-building plan and policy briefs to help policy-makers apply the framework. The framework has guided a pilot phase of WACDEP in eight countries – Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Ghana, Mozambique, Rwanda, Tunisia and Zimbabwe. In these countries, the framework has helped define national water planning. For example, WACDEP has helped Cameroon’s Ministry of Water to create a climate-resilient, five-year, Integrated water resources management, action plan. The Programme also supports the Ministry of Environment in integrating water security issues into the ‘National vulnerability and risk analysis report’.

CDKN is supporting the next stage of the programme, which aims to strengthen the institutional capacity to put the framework into practice among ministries and local governments in WACDEP countries.

Food security

A changing climate leads to changes in the frequency, intensity, spatial extent and duration of weather and climate events, and can result in unprecedented extremes, both through slow onset disasters (e.g. consecutive years of drought) and extreme events (e.g. heavy flooding). Many such events will have a direct impact on agricultural systems now and in the future, including through increased duration, frequency or intensity of heat waves, increased frequency of heavy precipitation in many regions, intensified droughts across some areas, upward trends in extreme coastal high-water levels, and changes in flood patterns. Crops, livestock and people will all be affected.

Agriculture is among the sectors most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and weather extremes because of its dependence on natural resources such as water and ecosystem services. Water supply for agriculture, for example, will be critical to sustain production and even more important to provide the increase in food production required for the world’s growing population.

Transformational approaches will be required in the management of natural resources, including new climate-smart agriculture policies, practices and tools, better use of climate science information in assessing risks and vulnerability, and increased financing for food security. ‘Low regret’ adaptation options typically include improvements to coping strategies (i.e. strategies to overcome adverse conditions and restore basic functionality in the short to medium term) or reductions in exposure to known future threats, such as better forecasting and warning systems. Other short-term adaptation strategies include diversifying livelihoods to spread risk, farming in different ecological niches, and risk pooling at the regional or national level to reduce financial exposure. Longer-term strategies include land rehabilitation, terracing and reforestation, measures to enhance water catchment and irrigation techniques, and the introduction of drought-resistant crop varieties.

In Nepal, farming has become a feminised occupation, as men migrate to the cities for work; farming has also become more difficult due to increasingly erratic rainfall and high temperatures. The threats of climate change to food security have therefore risen up the political agenda and have stimulated new government and donor investments (see box).

Climate impacts on food security: A driver for new agriculture practices in Nepal

“Climate-smart agriculture is really important for Nepal because it helps us to reconcile the two goals of food security and adaptation to climate change,” explains farming expert Bikash Paudel in a CDKN documentary film, Farmers of the future.

The threat of drought to crop yields and food security emerged as a major development concern and political priority during the Government of Nepal’s assessment of the economic impacts of climate change and a CDKN project to promote the uptake of climate-smart agriculture was one of the results. Thanks to the project, 300 women farmers from the high mountains, mid hills and Terai plains of Nepal are now being mentored in water-saving and climate-resilient practices, such as rainwater harvesting and drip irrigation systems; the latter have cut water use by 30 percent. Solar-powered pumps have revitalised irrigation systems and made fields far more productive, while also doing away with the need for polluting diesel pumps. The introduction of biofertilisers and bio-pest control has increased the yields, in some fields, by 15 to 20%.

Water-energy-food nexus

It is important to plan for increasing pressure on natural resources and resource scarcity in a changing climate, and the implications of these trends for the ‘water-energy-food’ nexus. Why are these three sectors together referred to as a ‘nexus’? Provision of food and freshwater to human populations depends intrinsically on the availability of freshwater as well as, to a certain extent, land for crops and water storage. Many energy systems that rely on water for power generation (such as hydropower) or for cooling may compete, in specific geographic areas, over the use of water. It is important for stakeholders to collectively recognise the changes in climate-related risks across these sectors and for robust institutional and governance processes to guide societies through the trade-offs in prioritising resource use.

Better governance of water-energy-food sectors can benefit Amazon security

As habitat destruction interacts with climate change, the concern is that the Amazon will be caught up in a set of ‘feedback loops’ that could dramatically speed up the pace of forest loss and degradation and bring the Amazonian biome to a point of no return. In an exclusive interview, Yolanda Kakabadse, senior strategic advisor to CDKN said:

“Climate change is the greatest challenge we will face in this century. Especially because it will impact health, water, food and energy security, and will increase vulnerability and risk for the region’s growing economies and populations. Climate change will transform the Amazon ecosystem. If climate impacts are not managed to avoid getting caught in a set of feedback loops, the transformation will be amplified until there is a point of no return. If we do nothing, climate change will bring devastating consequences and neither the Amazon nor the world will be as we know it. If we avoid this scenario and work together to build a resilient ecosystem, Amazonia can help us adapt better to climate change.

“A rainforest not only stores carbon, it has a natural ability to regulate and stabilise the climate. Just imagine the power of Amazonia, the largest rainforest on Earth. Protecting the Amazon can protect climate. In fact, that is precisely what the Amazon Vision seeks: to strengthen the protected areas systems of Amazonia shared by Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname and Venezuela, in order to increase the ecosystem’s resilience to the effects of climate change and to maintain the provision of environmental goods and services benefiting biodiversity, local communities and economies. The ‘Amazon security agenda’ will contribute to tackling climate change since it intends to guarantee water, food, health, energy and, of course, climate security throughout the Amazon biome.

“… All nine countries must have a pan-Amazon vision rather than a narrow country-focused one. This means sharing information to help informed decision-making, mapping and monitoring areas where water, energy, food or health security are most vulnerable, creating a regional development agenda, strengthening protected area systems, having common basin management policies and a joint zero-net deforestation target, among others. Only by having a common and coherent agenda they will be able to overcome all the pressures the Amazon is facing and ensure the wellbeing of the region.”

Reconstruction

Reconstruction after disaster (including after climate-related disasters) can provide the entry point for climate compatible development policies and programmes. When UNFCCC executive secretary Christiana Figureres visited Pakistan in the wake of the country’s devastating 2010 floods which displaced 20 million people, she urged the government to “build back better” – replacing previously vulnerable housing and rural infrastructure with more climate-resilient designs. A CDKN pilot project in Punjab province aimed to do exactly this (see box).

Indeed, when unavoidable weather-related disasters occur, some analysts have even suggested that reconstruction provides the entry point for GDP growth and job creation, when managed carefully, even if extreme weather does not strike again for some years. In The triple dividend of resilience (2015), Tanner et al. argue that “existing methods of appraising disaster risk management investments undervalue benefits associated with resilience. This is linked to the common perception that investing in disaster resilience will only yield benefits once disaster strikes. Decision-makers then view disaster risk management investments as a gamble that only pays off in the event of a disaster.”

When more sophisticated economic assessment is applied, decision-makers can identify more clearly the three dividends of investing in climate resilience and disaster risk management, namely:

- avoiding losses when disasters strike;

- stimulating economic activity thanks to reduced disaster risk; and

- achieving development co-benefits from specific disaster risk reduction investments.

The first dividend, the desire to avoid losses in the event of a repeat disaster, is a common motivation for climate-resilient investments. As an example of the second dividend, the authors note that the mere possibility of a disaster causes risk-averse households to stymie their entrepreneurship and long-term planning activities – whereas, diminishing the spectre of disaster can unleash some of this potential. On the third dividend, it is slowly becoming more widely recognised that investments in disaster reduction infrastructure can provide many worthwhile development benefits irrespective of when disaster strikes again: for instance, storm bunds may double as walkways.

Building back better after the Pakistani floods

CDKN supported the Punjab Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA) to prepare guidelines for rebuilding housing and infrastructure in rural areas that it is more resilient to climate extremes and disasters.

It is not just about climate resilience and disaster response though, the project also sought ways to integrate climate adaptation with low-carbon growth.

Pakistan has some history of including disaster risk-reduction measures in its building codes: after the 2005 earthquake in northern parts of the country, aspects of earthquake resilience were addressed. But national and provincial building codes have never got to grips with the risks from floods, temperature increase, energy shortages and extreme climate events. Rural areas are particularly lacking in such guidance and regulation.

With CDKN’s support and the expertise of engineering experts Mott MacDonald, the PDMA of Punjab oversaw development of rurally appropriate, climate compatible construction guidelines. These provide local planners with basic options for layout and building designs to reduce vulnerability and exposure to natural hazards, and improve the energy efficiency of buildings.

By engaging key authorities and stakeholders in the process, the PDMA has triggered communication across government departments on rural–urban planning issues and by-laws for local construction. A full consultation and consensus-building process is now taking place with district authorities and community planners.

Recreation and tourist amenities

Policies to bolster the recreational amenity of an area – for its own residents’ enjoyment or for its tourism value – may provide entry points for climate compatible development policies. CDKN-supported research and learning has documented this policy driver in the burgeoning ‘green tourism’ sector in Thailand and Viet Nam. In Chiang Mai, northern Thailand, as described in CDKN Inside Story Catalysing sustainable tourism: The case of Chiang Mai, a technical research team identified a range of options to decrease tourism-related greenhouse gas emissions in the city. Then a reference group representing local interests was consulted on the options. The group voted for options that married greenhouse gas reduction with local job security and also with cited motivations such as cleaner air, less motorised traffic congestion, green recreational spaces and even pride in a ‘green city’. Local deliberations recognised that a ‘green city’ is not only a valued commodity for local residents themselves, but also one of the principal attractions for the tourists on which much of the local economy (including sustained employment) depends.

Local priorities, local relevance

For local and subnational innovations in climate compatible development (or, alternatively, when it comes to delivering national mandates at local level, as further explored in Chapter 5), the relevance of the climate programme to local concerns is paramount. The case study of mainstreaming climate change into South Africa’s municipal development plans delivers a strong lesson about communicating local relevance: “Climate change considerations must be shown to be relevant to local priorities and circumstances. Developing county governments face many social, economic and environmental challenges and framing climate change action as a response to these challenges enables decision-makers to see such action as contributing to – rather than constraining – development.”

When stakeholders define the problem together, they have a basis for tackling the problem together

Ultimately, stakeholders need a participatory process to assess the costs and benefits associated with different options. One approach which has proven effective at doing so is the ‘Mitigation action plans and scenarios’ (MAPS) methodology. In the MAPS approach: ‘Learning and doing in the global South’, the facilitators explain how it “explores future pathways through the building of mitigation scenarios, and aims to create a better understanding of the economic, social and environmental implications of these different mitigation pathways. The researcher and stakeholder team seek to develop credible evidence that uses the specifics of their country’s political economy, and delivers scenarios to achieve relevant development goals (including mitigation).” The MAPS process has, at its heart, the ‘co-generation’ of knowledge so that researchers (scientific experts) and stakeholders (interest groups) go through a facilitated process to reach a common understanding of the different options for climate compatible development in their country – and their feasibility.

In Peru, the government decided to address climate change challenges through the project Planning for Climate Change (PlanCC), which adopts the MAPS process. PlanCC aims to build the technical and scientific bases, as well as capabilities, to explore the feasibility of a ‘clean’ or ‘low-carbon’ development in Peru and incorporate climate change approaches in the country’s development plan. Phase I of the project generated qualitative and quantitative evidence on possible climate change mitigation scenarios for the 2021-2050 period. In addition, it estimated the costs and potential for reducing emissions, co-benefits or indirect opportunities for society, environment and economy (e.g. alternative employment, reduction of pollution).

PlanCC has a strong ministerial mandate. It is chaired by a steering committee formed by the Ministry of the Environment, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Economy and Finance and the National Center of Strategic Planning (CEPLAN). In common with other parts of the MAPS Programme, PlanCC is seeking to establish a methodology for generating the evidence base for a long-term transition to robust economies that are both carbon efficient and climate resilient.

As a result of the initial phases of the process, 77 sectoral mitigation actions were proposed and validated by the stakeholder group, of which 33 were prioritised and presented to the government. Prioritisation was on the basis of co-benefits, feasibility and their contribution to poverty reduction. Mitigation options in solid waste, agriculture and transport have been selected and validated by a high-level inter-ministerial committee of the government. Some of this evidence has been considered and included into the country’s INDC as part of the UNFCCC process.

Manuel Pulgar-Vidal, the president of COP20 and Peruvian Minister of Environment, set out the importance of a consultative approach to planning as follows:

“The national contributions for 2015 need to be agreed in each country through national debate and within a solid policy framework that allows for full accountability over time.”

The right stakeholders must be at the table

Efforts to plan climate compatible development that involve the stakeholders affected by climate change and by climate policies have a significantly higher chance of success. Involving affected groups in vigorous public consultation and debate makes a tangible and positive difference to how policies are designed. Policies developed in this way are also more likely to win public support and be taken up and implemented.

Good consultation and participation in decision-making are nothing new. They are fundamental principles for environmental decision-making and for sound development. Such principles were enshrined in the Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters or ‘Aarhus Convention’ (1998). With its 46 signatories among European governments plus the European Union, the Aarhus Convention has provided a guiding framework for donor governments’ environment-related policies (see also ‘Aarhus Convention as a tool for enhancing the role of the public in tackling climate change’ by Jeremy Wates). The principles of deep civil society engagement in sustainable development decision-making were further underlined in the Rio+20 outcome document, signed by the world’s governments in Rio de Janeiro in 2012 (see Box).

'Future We Want – Outcome Document' of the Rio+20 Summit on Sustainable Development

“We underscore that broad public participation and access to information and judicial and administrative proceedings are essential to the promotion of sustainable development.

“Sustainable development requires the meaningful involvement and active participation of regional, national and subnational legislatures and judiciaries, and all major groups: women, children and youth, indigenous peoples, non-governmental organizations, local authorities, workers and trade unions, business and industry, the scientific and technological community, and farmers, as well as other stakeholders, including local communities, volunteer groups and foundations, migrants and families as well as older persons and persons with disabilities. In this regard, we agree to work more closely with the major groups and other stakeholders and encourage their active participation, as appropriate, in processes that contribute to decision-making, planning and implementation of policies and programmes for sustainable development at all levels.

“… We acknowledge the role of civil society and the importance of enabling all members of civil society to be actively engaged in sustainable development. We recognize that improved participation of civil society depends upon, inter alia, strengthening access to information and building civil society capacity and an enabling environment.”

However, there is a risk that principles of thorough public consultation and participation in decision-making could be cast aside as aid agencies, private businesses and governments grapple with climate change. That is because the pressure to act on climate change is immense and is growing every day – there is a risk of hurtling headlong into mitigation solutions that will deliver greenhouse gas emissions savings quickly and at least cost. But if programmes are not carefully designed, they could act to the detriment of human development needs and even undermine people’s capacity to adapt to climate impacts. These risks make it especially important to embrace the principles of public consultation, and participation of affected stakeholder groups in decision-making when it comes to climate compatible development.

Like many other forms of development, climate compatible development involves trade-offs. It takes a dialogue process among affected parties to address these difficult issues for present day needs, as well as information on how climate change could affect these resources in the future. For instance, many mitigation solutions – such as biofuel expansion, certain forms of hydropower and geothermal energy – demand land and water resources. How should this competition for scarce natural resources be weighed up against immediate human needs for food production, freshwater for drinking and sanitation, and land for settlement?

Several cases from CDKN’s experience illustrate how consultation with the general public, or with specifical representatives of affected stakeholder groups, can influence the design of policies – and make them attractive to a broader cross-section of social groups.

In Togo, HELIO International worked with the Government of Togo to devise a ‘smart energy path’ to increase access to energy in a low-carbon, environmentally sustainable way. The process invited stakeholder groups to debate, agree on priorities and plan a new programme to increase access to energy services. The facilitators of the process expected the participants to prioritise electricity supply to households (a conventional approach to rural electrification). However, household electricity came only in fourth place; the top three priorities ranked by stakeholders were all related to nutritious food and personal health: energy for access to clean water, electrification of health centres, and clean and efficient solutions for cooking and heating water (Working towards a smart energy path: Experience from Benin, Mali and Togo, 2015).

An innovative approach to urban planning in Maputo, Mozambique helped communities rank their development priorities in the context of a changing climate. The participatory process materially influenced the public understanding of climate impacts and ‘problems’, and the prioritisation of solutions (see Box).

Public Private People Partnerships for Climate Compatible Development – Maputo, Mozambique

The Public Private People Partnerships for Climate Compatible Development (P4D) project led a participatory urban planning process that recognised the capacity of citizens living in settlements to develop a collective vision for the future of their neighbourhood.

They formed a community planning committee which produced a ‘Community plan for climate change adaptation’ – with Maputo-based facilitators who received training to play this role. The facilitators provided check points, but the communities developed proposals, wrote the plan, presented it to other actors and made follow-up approaches to institutions for further support.

Neighbourhood residents showed what was really important to them: they proposed measures to improve the bairro’s waste management and drainage through community organisation, repairing networks to improve the water supply and improving waste management through a recycling centre. They also suggested the promotion of environmental education to, for example, learn about waste management and emergency responses to flooding. What is distinctive about all these home-grown solutions suggested by residents is that they identified interventions that would reduce the occurrence of urban flooding, spread of disease and threats to clean water during floods – issues that are core to their quality of life. They rejected the option of relocation because they believed it would have an unbearable impact on their livelihoods. The project created a shift away from passive participation in neighbourhood planning to active leadership and mediation.

The neighbourhood’s proposals have been presented to government institutions and private firms in Maputo and created opportunities for dialogue, in both informal meetings and public forums. Some policy-makers responded enthusiastically. There is no evidence of policy impact yet, but the municipality has embarked on deeper climate change planning processes following this project. Mozambique’s disaster management agency staff acknowledged that they have gained confidence in the way such participatory methods can involve local residents in climate change adaptation planning decisions. The project also highlighted that participatory planning requires sufficient allocation of time and money to undertake meaningful community consultation and a detailed scientific assessment of climate impacts.

Knowledge partnerships are essential for creating climate solutions

The Maputo example above shows how a common understanding of historic climate trends and future scenarios can provide the foundation for developing climate-resilient and low-carbon plans among affected stakeholders and decision-makers. Among the CDKN projects we reviewed, the most progress in planning for ‘future climate-proofed’ development was achieved where knowledge partnerships were established among experts both within and outside affected communities. It is important that local people, who are familiar with recent climate patterns and existing adaptive responses, are recognised as experts in their own right. Most of the cases analysed were distinguished by the presence of bridging institutions, or ‘knowledge intermediaries’, that helped to demystify and translate concepts of climate impacts, vulnerability and longer-term climate trends and solutions. In the Maputo case, the knowledge intermediaries were UK- and Maputo-based universities, which played a facilitation role with local leaders and community members.

In another example, the Regional Institute for Population Studies at the University of Ghana has played an instrumental role in translating concepts about climate trends and vulnerability for local communities (literally, from English to local languages, as well as by framing technical language in more accessible terms) (see Box).

The role of bridging institutions or knowledge intermediaries can include making climate science accessible to non-specialists (see ‘Knowledge brokers’, Chapter 2). Scientific knowledge on climate change hazards and the likely impacts at the subnational level often resides with national authorities and agencies. Making it easier for local actors and affected groups to access and understand the relevance of such information in the local context helps them to feed into decisions more effectively. How can this be done? The answer lies in finding engaging communications tools and messages that are appropriate to the audience.

In the city of Cartagena, Colombia, research partners behind the vulnerability assessment produced effective data visualisations that showed how much of the city’s historic and commercial property would be inundated by sea level rise in a matter of decades. They used these to engage business and local government leaders (CDKN Inside Story Embedding climate change resilience in coastal city planning and Plan 4C).

Knowledge partnerships assist urban development policy in coastal Ghana

The University of Ghana has been working to promote the use of climate change risk information in the country’s development strategies.

A project team supported by CDKN sought to tackle the following hurdles:

- Decisions on climate risk reduction and planning are too often top-down and so lack the local context and ownership that would be necessary to lead to effective action at the grassroots level.

- There are weak links between the national policy framework and district-level planning.

- There is a lack of clear policy directives or implementation plans for tackling climate risks at the district level.

Through approaches including multi-stakeholder workshops and field trips, the project helped national-level decision-makers to connect and empathise with local contexts and challenges, and communities to feel meaningfully included in policy design. On the basis of the research and round table discussions, three focal communities prepared contingency plans for dealing with climate and disaster risk. These community-level contingency plans are intended to inform district and regional preparedness plans and, ultimately, to contribute to national-level disaster risk management, helping make the process bottom-up as well as top-down.

Researchers and policy-makers did not prescribe adaptive practices. Rather, coastal communities were helped to define their own adaptation and resilience pathways through community-based ‘reciprocal learning’ processes.

A community-based risk screening tool, ‘Adaptation and livelihoods’, empowered local participants to articulate climate-related disaster risk reduction and planning. In turn, these co-productive learning activities validated and increased ownership over the emerging research results. Policy-makers and practitioners were not simply lectured on climate-related risk management, but had to think through challenges with activity-based, ‘learning by doing’ and dialogue-based round tables.

Participants used diverse communications tools and participatory methods, including drama, discussions, films, animations and environmental objects, to debate the challenges of coastal climate change impacts and form recommendations for mainstreaming climate disaster risk management into policy.

There are some early signs of the project influencing policy, and it seems to have achieved some success in changing the mindsets of key individuals at national level and even beyond. It is not yet possible, however, to ascertain what real impact this project will have. A crucial piece of learning from the experience is that stakeholder engagement in itself is not enough – the timing and nature of that engagement also plays a large part in determining a project’s success.

Women need to be empowered as equal partners with men, and socially disadvantaged groups should have a place at the planning table

The IPCC concludes that people who are socially, economically, culturally, politically, institutionally or otherwise marginalised in society are often highly vulnerable to climate change. Climate change impacts will slow economic growth, make poverty reduction more difficult, further erode food security, and prolong existing poverty traps and create new ones, particularly in urban areas and emerging hunger hotspots.

In India, the ‘National action plan on climate change’ recognises that women, already disadvantaged by the gender gap, will be particularly affected by climate change. However, it fails to include the gender dimension in its eight action-focused ‘missions’ that encompass both mitigation and adaptation strategies to deal with climate change.

CDKN partner Alternative Futures assessed four state action plans on climate change – Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal and Uttarakhand – through a gender- and rights-based lens. The project engaged with key stakeholders including officials, legislatures and the public to raise awareness of the gender dimension of climate change through robust research. The project was successful in getting the agreement of the central Ministry of Environment and Forests to incorporate gender dimensions in all state action plans. Some of the research material was included in the Government of India’s official submission to COP18 with respect to advancing gender balance in bodies established by the Convention and Kyoto Protocol and was included in the COP decision.

A parallel documentary film project, which invited Indian women to film each other talking about climate impacts, shows the resourcefulness of women within the context of poverty and socio-cultural constraints. The film is called Missing because women are currently ‘missing’ from the climate action plans. However, it illustrates that if women were to become full partners in climate change planning, their wellbeing, and that of broader society, would be substantially improved.CDKN commissioned a literature review that demonstrates how integrating gender-sensitive approaches in a programme’s design delivers the strongest overall results for climate compatible development – as opposed to trying to bolt on gender aspects later. (Lessons on the benefits of a gender-sensitive approach are further discussed in Chapter 5.) A short collection of video interviews with CDKN’s strategic advisors from Uganda, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Peru explores the differential impacts of climate change on women and the opportunities offered by gender sensitive climate planning.

A comprehensive research study commissioned by CDKN into the role of gender-sensitive approaches in delivering climate compatible development in Kenya, India and Peru (2015-16) found that when it comes to assessing vulnerability to climate change impacts and planning climate resilience interventions, gender-sensitive approaches are vital in recognising different people’s needs:

“[Gender-sensitive] analysis not only provides a more in-depth understanding of the effects of climate change. It also reveals the political, physical and socioeconomic reasons why men and women suffer and adapt differently to everyday climate-related challenges, extreme events and longer-term environmental changes.”

For example, according to Kratzer and Le Masson, in Peru, attention to gender-sensitive approaches allowed for better analysis of men’s and women’s roles and the physical, political and economic factors that make them more or less climate-vulnerable. Climate change may cause men to leave their families and migrate to find livelihood alternatives in urban areas. These movements cause changes in gender roles as women become fully responsible for taking care of the family’s basic needs, while the men risk becoming isolated or exploited in their new environments.

Farmers of the future, a documentary film exploring the increased agricultural burdens on women in Nepal and the opportunities for women to lead in climate-smart agriculture solutions, reflects similar dynamics. A short collection of video interviews with CDKN’s strategic advisors from Uganda, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia and Peru explores the differential impacts of climate change on women and the opportunities offered by gender-sensitive climate planning.

It is important to have the right planning tools

Over the past five years, there has been a proliferation in the number of climate compatible development planning tools. Such is the array of tools – ranging from complex, interactive online decision support systems to simple spreadsheet-based tools – that CDKN commissioned an analysis of the tools available. CDKN also worked with the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) to produce a digital guide to some of the planning tools available, searchable with simple, drop-down menus. This work has since been merged with an even more ambitious guide to climate-smart planning tools developed by the World Bank and a broader range of knowledge partners. Now the growing communities of practice that comprise the Low Emission Development Strategies Global Partnership (LEDS GP) is creating its own guidance to climate compatible planning tools for different sectors such as transport. A new ‘Development Impact Assessment toolkit’ helps users to find out which tools are available to evaluate the particular economic, social and environmental impacts of different low-emissions or ‘LEDS’ approaches.

The importance of having the right planning tools available is illustrated by the experiences of the small island states in the Caribbean. For decision-makers in the Caribbean, the impacts of climate change are all too apparent. In recent years, the region has suffered at the hands of climate-related extreme weather events such as hurricanes and flooding, and other climate-driven changes such as sea level rise and ocean warming. From infrastructure projects, through town planning and fisheries management, to tourism development, the question of how to continue to prosper in the face of climate change is a primary concern for policy-makers in the region. Integrating considerations of climate risk into the decision-making processes for legislators, planners, policy-makers and project leaders is a considerable challenge.

In order to provide some answers to these challenges, the Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre (CCCCC), with support from CDKN, designed the Caribbean Climate Online Risk and Adaptation TooL (CCORAL), a web-based tool designed to help decision-makers in the Caribbean integrate climate resilience into their decision-making and planning processes. The tool’s development included a thorough consultation process involving significant inputs from across the region. Critical inputs have been provided by government ministries in the four CCORAL pilot countries (Barbados, Belize, Jamaica and Suriname), non-governmental and civil society organisations, business and financial services sectors, universities and research institutions, and development partners. The new online support tool is an important step towards increasing the climate resilience of the region.

Training on CCORAL has taken place in 14 Caribbean countries to date. Grenada has integrated the use of CCORAL in its decision-making for capital projects since 2014. CDKN, Global Water Partnership and CCCCC have also supported development of the related CCORAL-Water tool, to apply risk management criteria to investment decisions in the climate-vulnerable water sector.

Building capacity to withstand climate-related shocks in Central America

The accumulated effects of climate change are already clear in Central America’s ‘Dry Corridor’ – a subtropical highland area stretching from Guatemala to Costa Rica.

A recent report states that an estimated 3 million Central Americans are struggling to feed themselves as a result of falling crop production, which is linked to drought, floods, extreme temperatures and sea level rise.

The CDKN-supported Climate Resilience and Food Security in Central America (CREFSCA) project has developed tools to help communities identify their climate vulnerabilities and take action to address it. The project’s main outputs were two decision-support tools, designed to enable community members and policy-makers to assess the vulnerability and resilience of food systems, develop resilience actions and generate indicators to monitor that resilience over time. The tools were developed and tested through an iterative process grounded in practical field applications.

“Food security is looked upon from a systemic perspective where issues like storage, related infrastructure, and other supporting natural and built-in elements are taken into account. The conceptual framework and CRiSTAL food security tool were very useful to identify and understand the impacts chains, how the climate impacts cascade through the food system,” said Alicia Natalia Zamudio of lead organisation the International Institute for Sustainable Development. “With this systems conceptual approach, we also produced the FIPAT [Food Security Indicator & Policy Analysis Tool], which focuses its analysis on the national and subnational levels, including public policies and their capacity to support resilience.”

During the project, local and regional governments received training to use these tools in their contexts, improving both their knowledge on climate change and their understanding of key concepts. “The communities we worked with were empowered by their better understanding of food security issues. They became more aware of some linkages and answers to questions that were not explicit before,” Zamudio said.

For example, users developed indicators to help them measure their resilience to climate change shocks, including: percentage of households with family orchards or gardens, which could determine the level of vegetable consumption and the diversity of food produced and eaten; percentage of households with more than one storage facility or percentage of households with refrigerated storage, which is linked to access to electricity and whether they can refrigerate and cook food; and percentage of paved roads, which increases access to food, as unpaved roads are even more vulnerable to climate shocks.

The tools were used to analyse climate risks to the food system, the results of which were used to design policies for the Mancomunidad Montaña El Gigante (Guatemala), a rural community that depends almost exclusively on agriculture. In Honduras, use of CRiSTAL has spread beyond the original project communities, because it is being used more widely by NGOs. The tools could soon be incorporated in the university curriculum of the Universidad Autonóma de Honduras (UNAH).

Developing countries must plan for tomorrow’s climate, not yesterday’s

When it comes to adapting to climate change, some governments and businesses are responding to the climate impacts felt today. They are increasing the climate resilience of building and infrastructure design and of development programmes – often in response to climate-related disasters. But this does not mean that they are looking ahead to anticipate the greater climate changes expected over coming decades. They need climate information and planning tools that will help them to build resilience to the likely challenges in the climate over the next 5-40 years, which is the horizon for major infrastructure investments being made today.

A study of how African governments are using climate information to shape development planning found that most projects focus on reducing existing vulnerabilities, rather than dealing with future risks. In general, “there are significant opportunities for integrating longer-term climate projections into policies and programmes,” the authors concluded.

In Gorakhpur district, India, the Gorakhpur Environmental Action Group has been working closely with government officials for decades to increase awareness of climate impacts on development. The group has been successful in convincing officials to integrate climate-related concerns into disaster risk management – the evidence that floods harm the property and livelihoods of the local population with increasing frequency, is clear ‘on the ground’: “Recent studies in the area, and climate projections indicate that the patterns of extreme rainfall are increasing. For example, one analysis shows an increase in the intensity of rainfall events by up to 33%, especially for longer duration events.” However, the team’s greater challenge was that, “To be effective, disaster management planning must include both current and projected climate change impacts.” A CDKN-supported project, documented in a new film, For a safer future: Climate resilience in India, has supported secondments of climate resilience experts to district government and a series of round table dialogues to deepen understanding and action on future climate planning.

Early pilot initiatives in developing countries to ‘climate proof’ – or ‘future proof’ – development must share their lessons widely to enable broader awareness and uptake of such approaches: future proofing approaches must become de rigeur for development investments in the years ahead. The costing of such adaptation and resilience measures inevitably emerges as a concern in project planning; in CDKN’s experience, the most promising pilot initiatives stress ‘low regret’ and ‘no regret’ adaptation investments, i.e. those which deliver both safeguards against future climate impacts and present-day development benefits (see also Triple dividend of resilience, above).

Future proofing Rwanda’s tea and coffee sectors

The Future Climate for Africa’ programme, a four-year, £20 m. programme funded by the UK Government (2016-2019), is supporting the generation of new climate information and decision-support tools to rise to these challenges.

The programme includes researching and publishing leading-edge climate projections for the continent – as explained in the recent Africa’s climate report – and road-testing the information and tools at numerous demonstration sites across Africa.

The future could look quite different to today: in Africa, the climate can be expected to be significantly different 40-50 years from now. Under a high-emissions scenario, average temperatures will rise more than 2°C, the threshold set in current international agreements, over most of the continent by the middle of the 21st century. Average temperatures will rise by more than 4°C across most areas in the late 21st century.

Until recently, Rwanda’s policies addressed the present ‘climate adaptation deficit’, based on current climate variability. These include floods and landslides, but also the effects of rainfall variability on agriculture, such as soil erosion and droughts. These impacts were recognised and have been integrated into national policy. In 2011, Rwanda launched a National Strategy for Climate Change and Low Carbon Development; the country has an operational climate and environment fund (called FONERWA for its French acronym, see Chapter 4); and the Government is also mainstreaming climate change into national and sector development plans.

Since 2015, a leading-edge pilot study has been underway in the country’s tea and coffee sectors to apply what is being termed a ‘decision-first’ approach to climate change adaptation. Tea and coffee crops are particularly physically vulnerable to temperature swings and rainfall extremes – and changes in the future climate could jeopardise the Government of Rwanda’s plans for doubling the land area under tea and coffee cultivation. The Tea and Coffee Climate Mainstreaming Project has been developing a pragmatic approach to ‘climate-proofing’ tea and coffee sector plans from early design, through the implementation and project finance stages.

Multi criteria decision analysis can optimise outcomes for climate and other sustainable development goals

While the above outline of economy-wide and sectoral entry points highlights the driving forces for many interventions, where climate compatible development goals may be pursued, decision-makers are still in need of tools that can help them select among multiple development options and navigate some of the inevitable trade-offs among social, economic, environmental and political-institutional outcomes that are inherent in different choices. Multi criteria decision analysis is a practical tool to support such decisions. The approach is discussed here with reference to a framework developed and illustrated by Khosla et al. A similar multi criteria approach has been developed and applied in West Africa’s energy sector by HELIO International (see below).

Khosla et al, note that in India, several national studies have tracked the achievement of multiple climate and environment, social and economic objectives once a development programme is underway, but “the primary challenge is to move to a methodology that allows an ex ante focus during decision-making.”

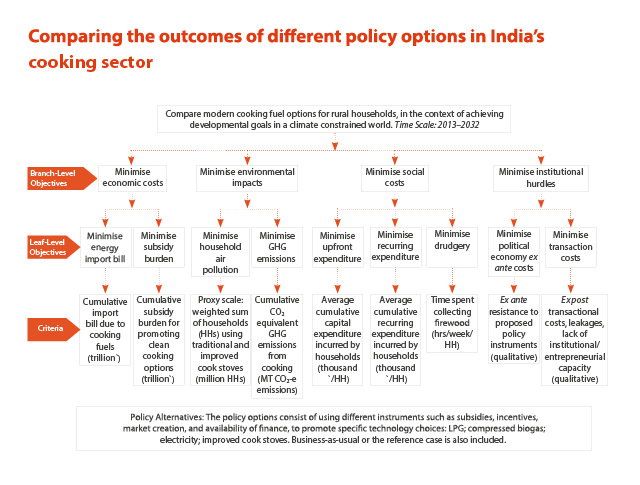

Demonstrating how this might be done, they apply the multi criteria decision approach to India’s cooking sector. The methodology requires decision-makers to state the policy objective – in this case, provision of cooking fuel to the millions of rural Indian households without reliable energy access. Associated objectives must then be defined, such as the desire to reduce greenhouse gas emissions via unsustainable fuelwood harvesting and to minimise women’s and children’s drudgery in seeking fuel wood, and decision-makers must weight all of these in terms of relative importance. Defining the primary policy goal and associated goals and weightings provides the opportunity for a consultative decision-making process with affected stakeholders.

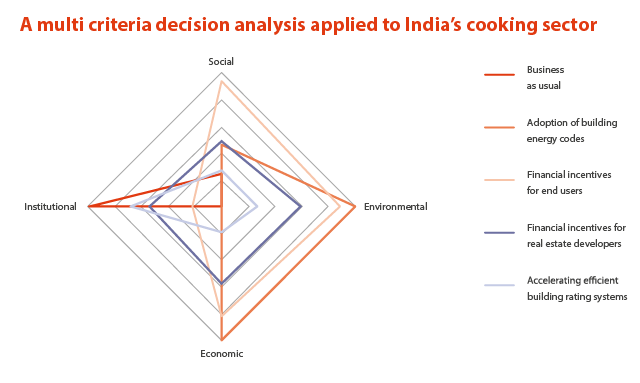

A decision tree showing the multiple objectives for the India cooking sector case study is shown in Figure 1 (below) and a preliminary spider diagram illustrating the economic, institutional, environmental and social outcomes of the alternative policy options in Figure 2. The larger the area created by the polygon, the better the policy option is at fulfilling multiple objectives.

Existing laws and policies can reinforce or undermine climate compatible development

Countries’ environment laws – and other relevant pieces of legislation – if properly enforced can play a fundamental role in achieving climate compatible development (see, for example CDKN’s Inside Story Bolivia’s Mother Earth law. By the same token, a country’s laws and policies often undermine climate compatible development. Mapping a country’s existing laws and policies and their effects on climate emissions and resilience are an essential part of the planning process.

The International Law Organization mapped Kenyan laws and policies as part of developing a national climate change action plan, part-funded by CDKN. This established that existing laws and policies, if properly resourced and implemented, can underpin environmental sustainability.

A case study of the Philippines’ climate change legislation found that the country’s Climate Change Act includes many far-sighted elements that aim to mainstream climate resilience into development. However, the authors find that “The success of the Climate Change Act in achieving climate compatible development depends on the interface between the Act and policy and legislation in related sectors.” In the Philippines’ case, mining projects, many of which may have taken place with inadequate consultation or without the consent of affected communities, run counter to the objectives of climate change legislation. “Negative social and environmental impacts on poor communities increases their vulnerability to climate change,” say the authors. “The Government continues to promote investment in coal, particularly by foreign investors, countering other mitigation aspects of the Climate Change Act. These conflicts are not addressed by the Climate Change Act, nor the National Climate Change Action Plan.”

The Future Climate for Africa scoping phase found “many initiatives aimed at promoting socioeconomic development can, whether intentionally or not, play a central role in tackling the root causes of vulnerability to climate change. For example, in Zambia the National Climate Change Secretariat and the ‘Pilot Project for Climate Resilience’ are seen as the most prominent actors driving the climate agenda forward. Yet other initiatives and investments, by a wide range of civil society and private sector entities in Zambia (most notably mining and real estate developers), are playing a central role in determining the vulnerability and ability to adapt to climate change of different social groups. Such companies’ activities are overlooked in high-profile national climate change planning. With this mind, any consideration of climate information in long-term decision-making has to recognise the role and interplay of climate change with wider drivers of development.”

Supportive public expenditure and fiscal policies are integral to climate compatible development

Climate change needs to be seen primarily as an economic concern that warrants attention by national ministries of finance and planning, and local counterparts. Fiscal policies play an important role in guiding investment decisions towards low-emissions and climate-resilient options.

As the organisers of the Green Growth Knowledge Platform Conference (2015) on fiscal policies said, “By reflecting the cost of externalities from natural resource use in the prices of goods and services, fiscal policy sends the right signal to the market. Such signals then stimulate a shift in production, consumption and investment to lower-carbon and socially inclusive options. Moreover, fiscal reforms aimed at removing perverse subsidies to polluting activities and unsustainable use of limited resources can not only create fiscal space for investing in development priorities, but can also generate revenues for nurturing the environment.”

This certainly holds true in most low-income countries where the use of fiscal instruments to meet environmental objectives has been rather limited. In many cases, the approach to pollution monitoring and control has mostly been in the form of legislation-based command-and-control measures. Fiscal instruments help implement such policies and can also address issues of fairness and equity, and provide incentives for behavioural change. This needs to be supported by an integrated and consultative approach reflecting good governance principles. In the long run, fiscal policies need popular support and trust. There were calls for sequenced introduction of policies rather than shock therapy, which in most cases has not worked unless the hardest hit have been properly compensated.

CDKN’s Inside Stories on the expansion of renewable energy in Thailand and the support for solar power in India show how government investment in nascent green industries can support a marked shift in private investments.

Thailand was among the first countries in Asia to introduce incentive policies for the generation of electricity from renewable energy sources, leading to rapid growth, particularly in the solar power sector. Programmes for small and very small power producers created predictable conditions for renewable energy investors to sell electricity to the grid. The ‘Adder’, a feed-in premium, guarantees higher rates for renewable energy, making the investments profitable. Thailand also regularly updates technical regulations, provides preferential financing, and invests in research and training. Civil society involvement strengthened and improved renewable energy policies. Outside expertise and links to international networks brought by civil society experts were crucial for the design and approval of the incentive measures.

A study of India’s Jawaharlal Nehru Solar Mission, which represents a national commitment to a secure investment regime for solar energy, showed that such a commitment can encourage project developers and financial institutions to take the early risks necessary for rapid diffusion of solar technology. Competitive bidding can rapidly drive down solar tariffs. However, the way that the pilot phase of the mission was designed led to a profusion of bids including some from under-qualified firms. This yielded some important lessons about the design of such financial incentives, including the finding that bidding conditions should be designed to ensure the selection of developers who are qualified and best able to innovate.

Public expenditure supports climate action from national to local level: The case of the Philippines

The Philippines’ national Climate Change Commission developed a National Framework Strategy on Climate Change in 2010 and a ‘National climate change action plan’ in 2011.

The framework strategy provides a roadmap for increasing the country’s social and economic adaptive capacity, the resilience of its ecosystems, and the best use of mitigation and finance opportunities. The action plan outlines programmes of action for climate change adaptation and mitigation, with seven priority areas: food security, water sufficiency, ecosystem and environmental stability, human security, sustainable energy, climate-smart industries and services, and knowledge and capacity development. The initial period (2011-2016) is focused on vulnerability assessments, identifying ‘ecotowns’ (places where climate compatible development can be modelled and demonstrated) and undertaking research and development to support renewable energy and sustainable transport systems. Implementation of this agenda requires government financing, multi-stakeholder partnerships and capacity building.

A key part of the action plan is support for local governments to design and deliver local climate change action plans. The national commission is tasked with helping these local governments to meet the human resource and financial challenges – for which it extends direct technical assistance and funding; local governments are also expected to redirect a portion of their annual internal revenue allocation to general programming.

The Climate Change Act requires government financial institutions to provide local government units with preferential loan packages for climate change activities. The Disaster Management Assistance Fund offers loans to local governments at low rates (3-5%). It aims to provide timely financial support for initiatives to manage disaster risk and damage. (This fund is additional to a Local Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Fund, the bulk of which comes from general appropriations or the national budget and local governments’ allocation of internal revenue.)

Source: Excerpted from Lofts, K. and A. Kenny (2012).

Labour policies can accelerate climate compatible development

CDKN’s Inside Stories that document large-scale sectoral transitions highlight the need for labour market policies to support such transitions. This is almost the reverse of the preceding point about possibilities for knowledge partnerships and co-creation of appropriate technologies at local levels. When it comes to larger-scale industrial transitions that involve the adoption of new technologies – particularly in manufacturing and service sectors – the domestic skills base and requirements for worker training are important considerations.

India’s energy efficiency programme (mentioned above) benefits not only from the extensive history of related policy and regulation on which it was built, but also from the considerable human resource base that exists to support it. The author found that “existing capacity – a result of efforts over the last 25 years – provided a pool of experts to tap during planning and implementation” of this energy efficiency initiative (CDKN Inside Story Creating market support for energy efficiency: India’s Perform, Achieve and Trade scheme).

By contrast, Kenya’s recent experience with trying to ramp up its installed geothermal power capacity has revealed challenges. A very limited pool of workers with the requisite specialist skills has proved a constraint to the sub-sector’s development, as described in the CDKN Inside Story Harnessing geothermal energy: the case of Kenya. Even if bringing in foreign talent is an option in the short term, it is not desirable; targeted labour and education policies will be needed to address the skills shortfall in the medium to long term.

A CDKN case study on developing a NAMA in West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia documents how independent power producers have requested training support to be ready to bid for government tenders in small-scale distributed renewable energy.